There I was, sitting in front of a window, half of it blocked by a computer screen and the rest covered with beautiful rain droplets—the perfect stimuli for one more coffee! But I told myself no; first, let me post this one article, share it in a few Facebook groups, and if at least 100 people are there within 15 to 20 minutes, then I will go for that coffee. How could I be so sure it was going to work? That “sureness” wasn’t just a hunch; it was a claim. In the world of science and data, this is referred to as a hypothesis. But before I could take that first sip, I had to put my prediction through a rigorous mental framework where “proof” is harder to come by than you might think.

Even when I didn’t know anything about hypothesis testing, in 9th grade, I had proved many math theorems. At first, I assumed the opposite of what I was trying to prove, and then I proved that opposite claim to be false. Therefore, the opposite of that false claim is true. This is what we call proof by contradiction. Hypothesis testing is a little bit similar to this, but the biggest difference is that math is an absolute thing—it is a proven truth. A hypothesis is more of a real-life phenomenon, and we all know how messy real life is! Think of hypothesis testing as a grown-up

I am going to define null and alternate hypothesis, the null hypothesis is a status quo, no change, alternate one is the claim I am making.

- H0: There is no change in web traffic on my website just because I have posted a new article.

- H1: In 20 minutes, I will have 100 people on my website through the new article I posted.

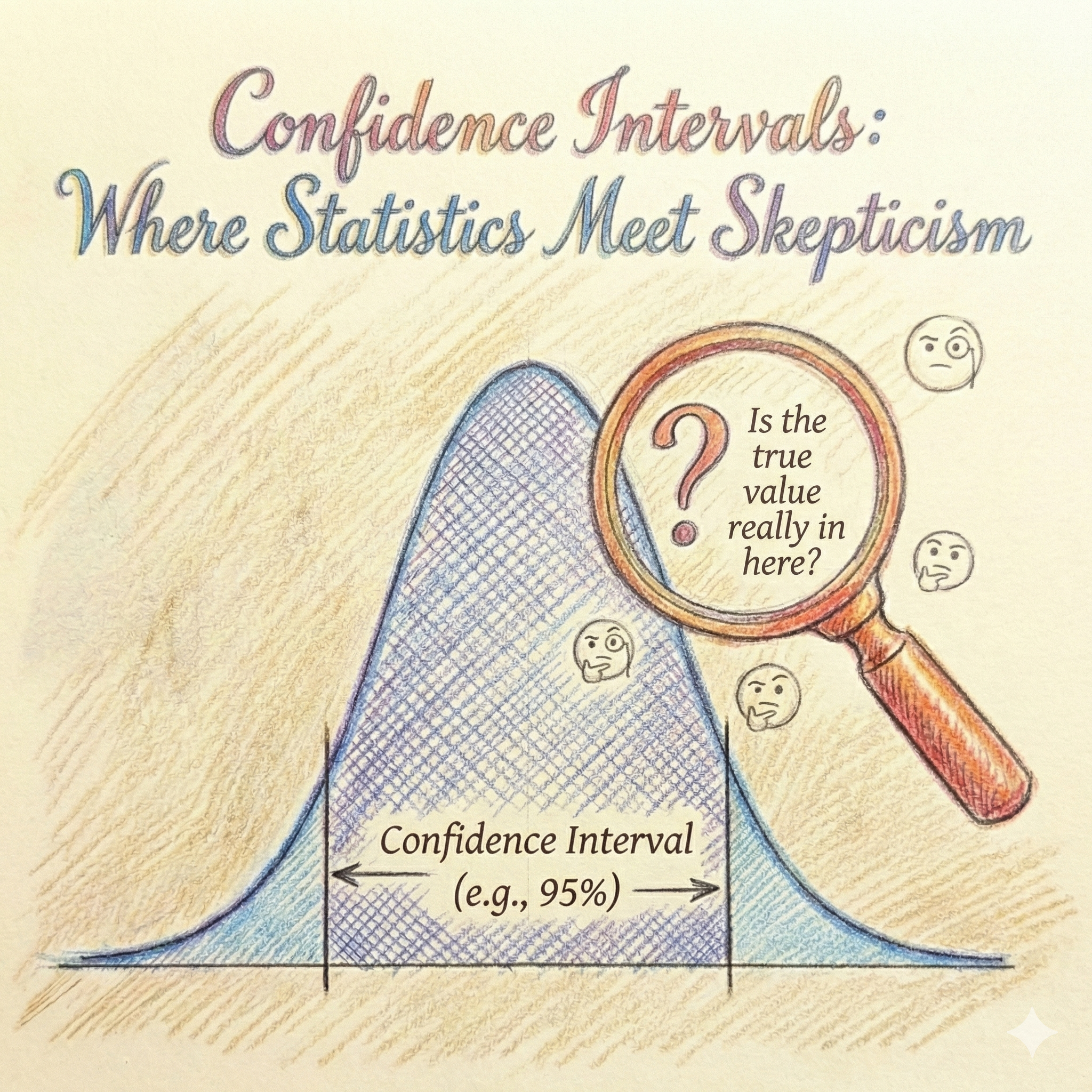

Now, most people stop here and ignore two very important aspects of hypothesis testing. I have heard many intelligent techies saying, “So we accept the null hypothesis.” I jumped out of my chair, screaming “NO!” You cannot say so. But most of the time, we were screens apart; I was muted with my video disabled, and I chose not to hurt the techie’s ego so that I could learn more tech stuff from them! So, here they are:

1) The hypothesis must be able to be proven wrong (Falsifiability):

My little one was teaching me animal alphabets and he said “U” is for unicorn, to which I protested; a unicorn is a mythical creature and not an animal. I have never seen a real unicorn; they are neither in the jungle nor in the zoo; they are not even on farms. To this, he said, “Mummy, a unicorn appears to those who have a pure heart.” (I thought, thank God he didn’t say, “Mummy, a unicorn appears to those who have a pure heart and not a cynical mind!”) Now, I have no way to prove scientifically that I have a pure heart! But do I need to prove it? “Burden of proof lies on whom?” is the next very important question.

This reminded me of a Medium article, “The Enduring Charm of Russell’s Teapot.” As it mentioned, if he claimed a tiny china teapot was orbiting the sun between Earth and Mars, but it was too small for telescopes to see, no one could prove him wrong. But just because it can’t be proven wrong doesn’t mean we should believe it’s there! He made his point clear that the burden of proof lies with the person making a claim; the burden of proof is not on the person to whom you want to prove something. This is very true for hypothesis testing too. It must be falsifiable, and the burden of proof lies with the one who comes up with the claim—aka the alternative hypothesis.

2) No one can “accept” the null hypothesis:

Let’s say that in 20 minutes only 10 people visit my website. Now, if I say I “accept” the null hypothesis, it implies I’ve proven there is no change in website traffic due to my blog post. But statistically speaking, it actually means I simply don’t have enough evidence to reject the assumption that my blog post doesn’t bring traffic.

Have you ever heard a judge saying a defendant is “innocent”? A judge always says the defendant is “not guilty,” and that means the prosecutor didn’t present enough evidence to prove that the person is guilty. In a nutshell: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

What happened to my coffee?

So, as I sat there watching the rain droplets and waiting for my coffee, I wasn’t just looking at a screen—I was running an experiment. I had a falsifiable claim, and I was waiting to see if my data would give me the “green light” to reject the status quo and finally head to the café.

Actually, I did!